Cosmic Concepts

For our 12th issue, Claire Sawers picked out the best responses from the worlds of literature, film and music, to the concept of outer space. Illustrations by Ollie Hoff and Bethany Thompson.

Solaris - Andrei Tarkovsky

Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 sci-fi film (not to be confused with the George Clooney/ Steven Soderbergh remake) remains an untouchable piece of psychedelic cinema, set in the near future, on a space station orbiting the planet Solaris. One movie poster from the time described Solaris as, ‘A planet where nightmares come true.’ A rewarding head-wrecker, its trippy plotline, taken from Polish author Stanislaw Lem’s sci-fi novel, explores grief, memory, suicide, dreams, alien life and mind reading planets in a way that is hard to shake off for days afterwards. Visually, philosophically and psychologically - a sci-fi masterpiece.

The Book Of Strange New Things - Michel Faber

Michel Faber’s 2014 novel about a Christian missionary’s voyage to another planet is part dystopian travelogue, part epistolary love story. In it, Peter and Bea are separated while Peter goes to preach to the indigenous people of Oasis; a foetus-faced species who speak with otherworldly, asthmatic voices, sounding like ‘a field of rain-sodden lettuces being cleared by a machete’. Faber wrote the book while dealing with his wife’s diagnosis with a rare, terminal cancer, and uses the metaphor of outer space to explore the realities of long distance love and death. On the surface, The Book of Strange New Things reads like an Orwellian bad dream, as if JG Ballard and Kurt Vonnegut found themselves wandering around a sterile space base filled with piped-in Patsy Cline songs, maggot-based hybrid foods and out-of-date lesbian porn mags. It’s a morose, matter-of-fact allegory on modern life, lightened up by Faber’s gentle wisdom.

Acme Novelty Library #3 - Chris Ware

This graphic novel by Chris Ware, the Chicago illustrator who also brought you Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth, is a science fiction story about a space mission to colonise Mars. For his 19th instalment in his Acme series, Ware rolls more of his trademark themes - unending loneliness, chronic emotional clumsiness, regular existential meltdowns - and his recognisable layouts and beautiful drawing style, into the context of outer space.

The Clangers - Oliver Postgate

The original 1960s kids TV show (not to be confused with the much less magical £5 million remake in 2015) ran on BBC 1 between 1969 and 1974, and imagined a peaceful family of pink knitted mice living in outer space, far away from the chaos of planet Earth. The show was the brainchild of the supremely talented Oliver Postgate, a pioneer in children’s storytelling who also happened to be a conscientious objector, anti nuclear campaigner, inventor and grandson of the leader of the Labour Party in the 1920s.

His politics informed his delicious, utopian visions - he also devised Ivor the Engine, Bagpuss and Noggin the Nog. The Clangers featured an exceptional array of sound effects, and a score written by Vernon Elliott. The Clangers were peaceful, tiny, pink, knitted mice who lived off green soup and blue string pudding, and their characters’ voices were performed on swanee whistles, and backed up by celestial bells, harps, flutes and glockenspiels.

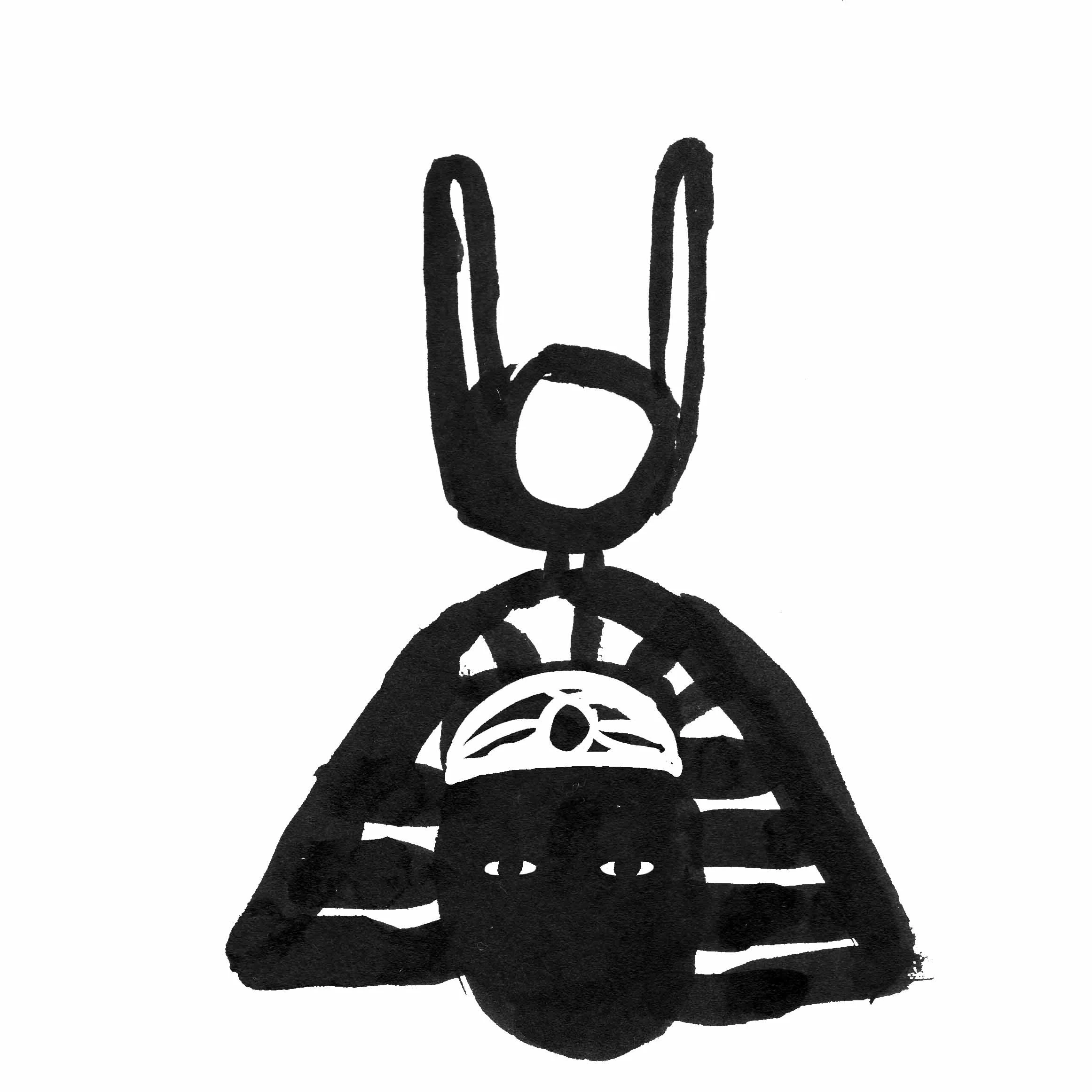

Space Is The Place - Sun Ra

‘The Black Man in the Cosmos’ was a course taught at the University of California, Berkeley in 1971. Artist-in-residence Herman Poole Blount, better known as Sun Ra, leader of cosmic-free-jazzers Sun Ra Arkestra, gave lectures as part of the Afro-American Studies course. His Black Man in the Cosmos lectures (audio versions of them still float about the internet) blended together ancient Egyptian mythology, occult philosophy, astrology and science fiction - to paint his radical Afrocentric vision of the world. Space is the Place was the trippy, tropical sci-fi film based on those visions, filmed around Oakland and San Francisco and released the year after the Berkeley lectures. In it, black people have left behind the violence and chaos of planet earth and started a new colony in space. It features the Arkestra’s outstanding trademark Egypt-meets-outer space costumes, and outlines their far-reaching visions for black power, through his idea of music as a parallel universe for black people to escape into. The film was followed soon after by the album of the same name, full of the Arkestra’s space-travelling wigouts and frilly, afro-futurist freakouts.